The history of racial oppression and lynching in the U.S. South has, civil rights advocate Martin Luther King III writes, “too frequently … gone untold and unaddressed.” But, he says in an April 17, 2021 op-ed in USA Today, Virginia’s repeal of the death penalty “shows us what is possible when we confront this country’s racist past, and acknowledge how racism permeates this country’s practices and laws.”

King (pictured), the eldest son of civil rights icons Coretta Scott King and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., has long championed death-penalty abolition. “As a Black man, born and raised in the South, this issue is deeply personal to me,” he says. King’s father and grandmother were murdered in politically motivated racial hate crimes.

“Both of these were heinous crimes,” King writes, “but despite our immeasurable grief, our faith and the racist roots of capital punishment led my family to reject the death penalty. You see, the death penalty was never intended to be used to give Black families like mine so-called justice or to show that society values Black life. Getting the death penalty in response to wrongs committed against my loved ones would not bring them back; it would have only tied their legacy to a deeply racist system.”

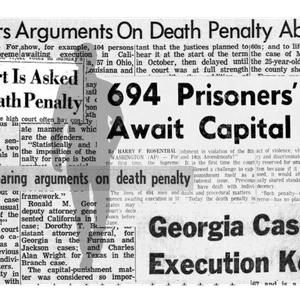

King says that “[f]or far too long, policymakers have shied away from open and honest discussions about capital punishment’s deep connection to lynching, Jim Crow laws and racial oppression.” Citing Richmond Times-Dispatch coverage of the Death Penalty Information Center’s September 2020 report, Enduring Injustice: The Persistence of Racial Discrimination in the U.S. Death Penalty, King notes that “Virginia’s history of racial discrimination in the death penalty is extensive,” stretching back into the 17th century.

A DPIC analysis of Virginia’s death-penalty practices has documented that 298 of the 377 individuals executed by the commonwealth in the 20th century — nearly 80% — were defendants of color. All 73 individuals executed last century for crimes that did not result in death — rape, robbery, or attempted rape — were Black.

“Lawmakers claimed they needed the death penalty to placate white mobs who wanted to continue using lynchings to maintain racial control,” King writes. He notes that historically “a defendant was more likely to face the death penalty if the victim was white than if the victim was Black” and race, he says, “continues to influence who is convicted and sentenced to die.”

Calling Virginia “the former home of the Confederacy,” King predicted that “[i]f we shine a light on any of the other Southern states that were known for high rates of lynchings, we are likely to find plenty of similarities. Lawmakers in these states,” he said, “should also be prepared for their racist death penalty practices to be exposed for all to see.”

“Ending capital punishment in Virginia is a decisive step toward the racial reckoning that our country desperately needs,” King concludes. “The rest of the South should follow suit.”

Sources

Martin Luther King III, MLK III: What we can learn from Virginia decision to end the death penalty, USA Today, April 17, 2021.

Race

Jun 14, 2024

Remembering the Execution of 14-year-old George Stinney, 80 Years Later

History of the Death Penalty

May 15, 2024